Interning in the Archive

Plain Sight Archive intern Jhelene Shaw spent a semester on the trail of underacknowledged Pop and Photorealist artist Idelle Weber (1932–2020). Through archives in Washington, D.C. and Los Angeles, she traced Weber’s chameleonic career from teenaged Abstract Expressionist to octogenarian portraitist. Discover highlights from the search to illuminate the painter and sculptor’s fascinating seven-decade career.

Idelle Weber: Forgotten Pop Sibyl

by Jhelene Shaw

[Figure 1] Idelle Weber on a cruise in Greece, 1967. Photo by Julian Weber. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber.

Initially written off early in her career as a mere future housewife, Idelle Weber refused to take no for an answer. She fought her way into the inner circle of New York’s Pop scene – only to watch herself written out of its history. In 1993, critic Hilton Kramer opined that, “There were no women in the Pop Art movement, which was an exclusively male phenomena.”1 Nearly four decades into her career as a working artist by that time, Weber took Kramer to task in a letter to the editor: “In addition to myself there was Marjorie Strider, Rosalyn Drexler, and Marisol.”2

And yet these artists and their many talented women contemporaries waited another two decades for any significant scholarly or public interest in their Pop careers. They finally enjoyed a well-deserved – if brief – 2010s renaissance. Curators and collectors thrilled as Weber, on the cusp of turning 80, pulled canvas after masterful, forgotten canvas out of storage – powerful reminders of just how present and central she had been in the Pop scene.

Despite this reckoning of one of the most well-respected and well-connected women in Pop, Weber’s work is still relatively little-known and undervalued compared to her male peers’. Though she has been collected by the likes of the Museum of Modern Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Smithsonian’s American Art Museum, her pieces are, to a one, “not on view.”3

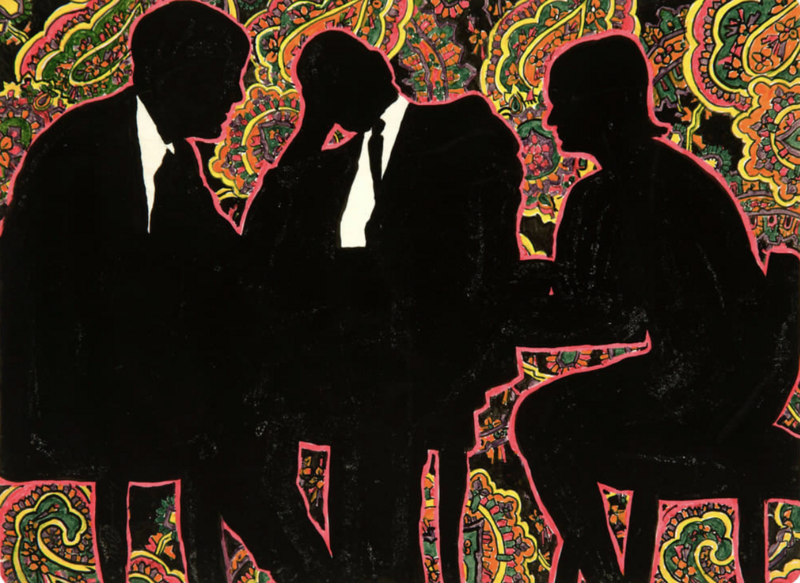

[Figure 2] Idelle Weber, “Double-Sided,” 1961–62. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber / Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Bread Crumbs

This sidelined body of work is filled with incisive social critique by an artist who continually defied expectations. It was a researcher’s siren song. Initially drawn to Idelle’s silhouettes, I soon discovered numerous dramatically different eras within her oeuvre. I became increasingly fascinated by the woman behind them. If Idelle’s Pop pieces are criminally underappreciated, they nevertheless cast a long shadow over her other equally intriguing work. Finding no comprehensive overview of her entire career, I set out to puzzle together the archival pieces.1

Here I offer a glimpse into Idelle’s life and work, but these amazing stories nevertheless only scratch the surface. More obscured than truly invisible in the archive, Weber nevertheless left relatively few clues in her donated papers and sketchbooks. Recent contact with her estate has opened new avenues of inquiry which will hopefully lead to the full biography she so richly deserves. Updates will follow, but for now – meet Idelle Weber.

[Figure 3] Weber poses in her Brooklyn studio with her painting “Downtown,” 1962. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber.

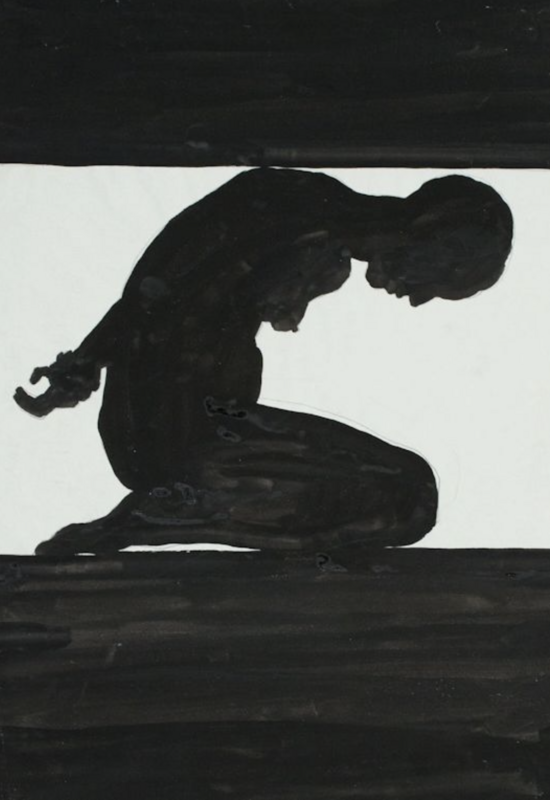

[Figure 4] Idelle Weber “Blocked,” 1965, work on paper. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber / Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

A Sibyl is Born

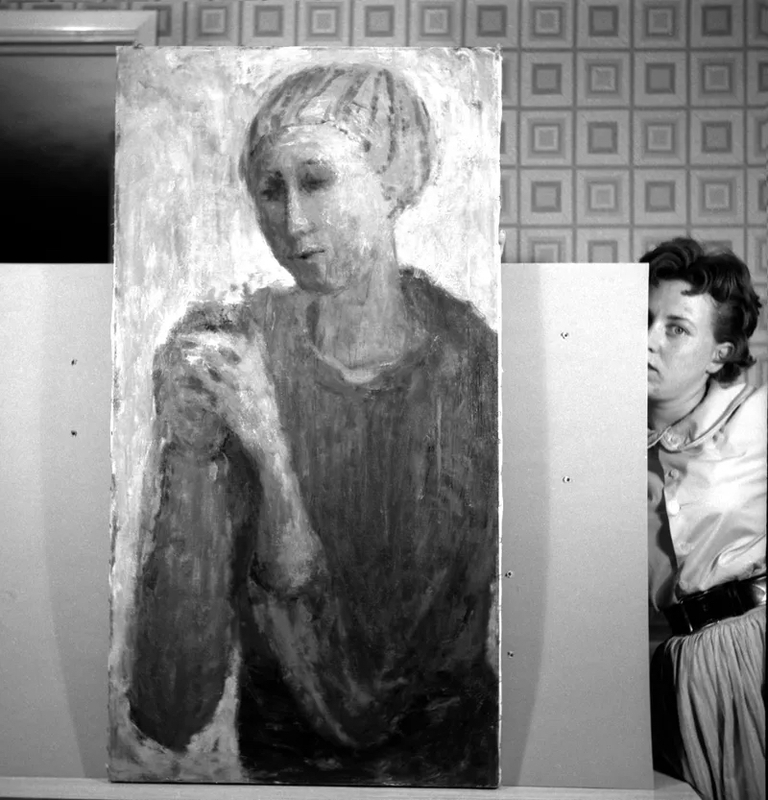

[Figure 5] Idelle Weber peeks out from behind an early, untitled work, 1950s. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber.

Weber was born Tess Pasternack in Chicago in 1932 and became Idelle Lois Feinberg in 1933 when she was adopted by parents Earl and Minna. Her Brownie camera and a much-loved magnifying glass helped foster Weber’s eye for detail and initiated a lifelong practice of photography and close observation. She clipped articles, photos, comics, and ads for her scrapbooks, predicting in some small way her future fascination with commercial and pop cultural imagery.

In 1940, the family relocated to Beverly Hills. Weber missed the Art Institute of Chicago and her beloved Rembrandts and Renoirs. According to Weber, the LA of her youth had only “one museum downtown that had very little.”1 She instead relied on visits to wealthy neighbors’ private collections. It was here she first fell in love with Matisse’s bold colors.

At twelve, Weber was too young to attend LA’s famous Chouinard Art Institute. Instead, she took weekly private lessons with a man who “terrified” her. These would be the recurring themes of her career, as she struggled under the tutelage of tempestuous male mentors and faced rejection based on her age and gender.

-

Unless otherwise noted, all direct quotes are from: Idelle Weber, interview by Christopher Kandel, March 8, 1982, Irving Sandler interviews and papers, 1944-2017, box 3, item 7, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. ↩︎

New York Calling

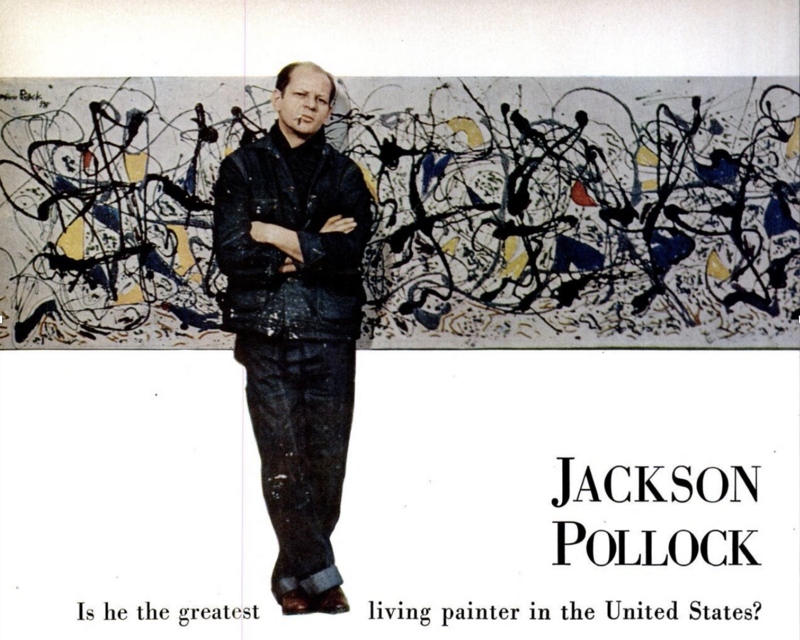

According to Weber, “My first realization of the New York scene was the article in Life magazine about Jackson Pollock” (see fig.6). She was awed, and wrote a high school thesis comparing Pollock to her favorite artist, Edward Hopper. Idelle attended Scripps College and then the University of California, Los Angeles. Most of her instructors were male, eccentric, and demanding, but Weber excelled, graduating with her bachelor’s as well as a master’s degree in art education in 1955. Her surviving works from this time are mostly moody charcoal portraits.

Weber was the lone woman artist in her early-career LA cohort. “Women had almost no say or involvement in that group… Unless you were sleeping with the artists in the area, you just were not involved,” she recalled. Weber drew a hard line between herself and these men – as well as a bright yellow one marking the sanctity of her shared studio space.

The “notoriously macho” Ferus Gallery emerged from this climate in 1957.1 Ferus later debuted Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s Soup Cans” in the artist’s first major West Coast exhibition, but never showed Idelle, who had often unlocked her studio to find gallery founder Walter Hopps sleeping in the back. This kind of sexist dismissal – even from friends and acquaintances – would also prove a continuing theme in Weber’s career.

“Blown apart” by Abstract Expressionist slides imported from New York, Idelle realized, “I’m not getting what I need here.” Paintings by Josef Albers, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, and Franz Kline beckoned her to New York, where she would soon come face to face with several of these men.

-

Sid Sachs, “Idelle Weber: New Realist,” in Idelle Weber: The Pop Years (New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 2013), 7. ↩︎

[Figure 6] “Jackson Pollock: Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” Life. August 8, 1949.

[Figure 7] Idelle Weber “Observation,” 1953. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

New York Realized

[Figure 8] Idelle Weber, “Observation of Sound,” 1955, charcoal on paper. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Idelle made her first trip to New York to debut “Observation of Sound” in MoMA’s 1956 juried drawings show (see fig.8). On her first day in New York, Idelle saw her charcoal hanging alongside pieces by Josef Albers and Ellsworth Kelly, in what was also the latter’s first major show. On her second day, she met her future husband of fifty years, fellow Californian Julian Weber. On her third day, she volunteered to babysit Mark Rothko’s daughter. Unsurprisingly, she decided to gamble on what might happen on fourth, fifth, and subsequent days: “I told my parents, ‘Send my clothes – I’m staying.’”

Claiming to design sets, Idelle moved in next door to MoMA, rooming with two Rockettes at the famous Rehearsal Club Boarding House. She and Julian soon married and moved to Brooklyn Heights, where their son Todd was born. Weber pivoted dramatically, filling canvas after canvas with all-gray color studies. She shaded gray into blue and red, testing the boundaries of color and living her maxim that “every inch of surface was important” (see fig.9).

Gallerists praised her work effusively without signing her. One dealer spoke for the rest when he informed Weber, “I don’t show women… They get married, and they have children.” She then approached Robert Motherwell at Hunter College, hoping to audit one of his classes. He loved her work. Yet as soon as he found out she was married and planning to have children, Motherwell demurred: “Once you’re married, once you have children, you stop painting… Don’t bother.” Instead, Weber joined the Art Students League and worked with Theodoros Stamos, another brilliant but cruel teacher.

Weber invited dealers to her home studio for visits timed carefully to coincide with Todd’s naps. Having faced such immediate rejection upon her arrival in New York, Weber was paranoid: “They never knew. I mean, it just would have been the end of it” had Todd made a peep.1 Soon new baby Suzanne joined the family, as Idelle continued to defy the art community’s expectations: “You weren’t supposed to have children at all then.”2

-

Glenn Holstein, “Seductive Subversion: Idelle Weber,” 2010, Pew Center for Arts and Heritage. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

[Figure 9] Idelle Weber, Untitled, 1957-58. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

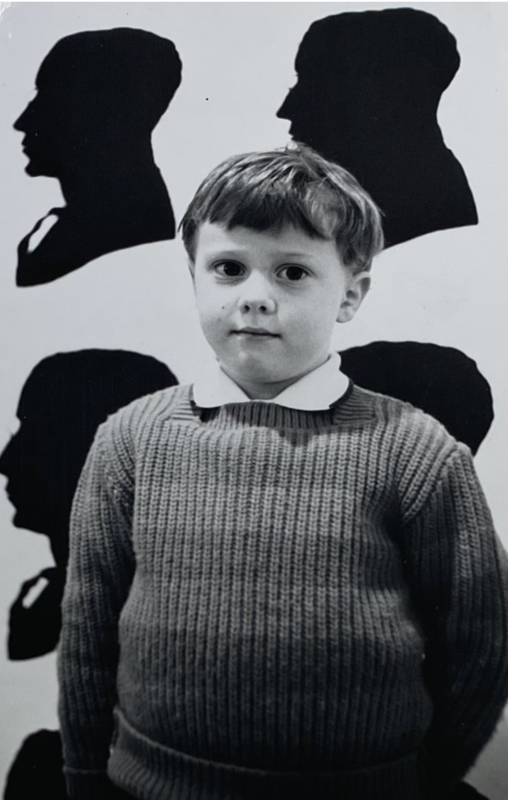

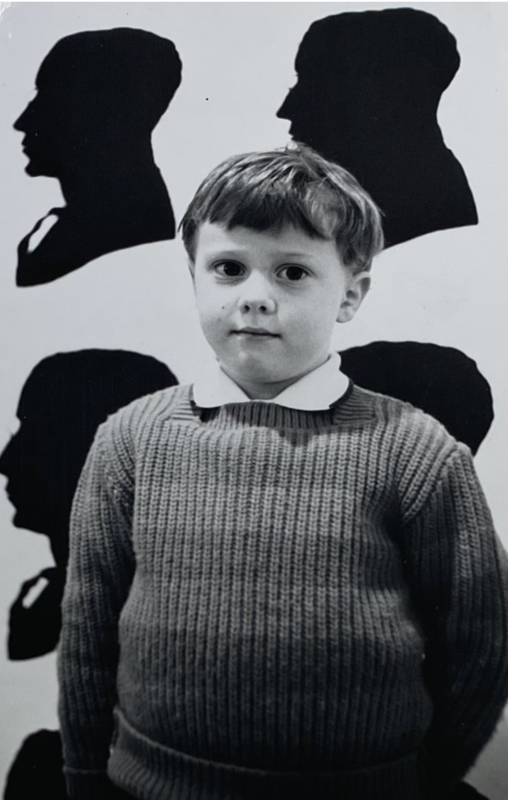

[Figure 10] Todd Weber in front of “Downtown,” 1963. Photo by Idelle Weber. Idelle Weber papers, 1963–1981, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[Figure 9] Idelle Weber, Untitled, 1957-58. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

[Figure 10] Todd Weber in front of “Downtown,” 1963. Photo by Idelle Weber. Idelle Weber papers, 1963–1981, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

A Vision in Black and White

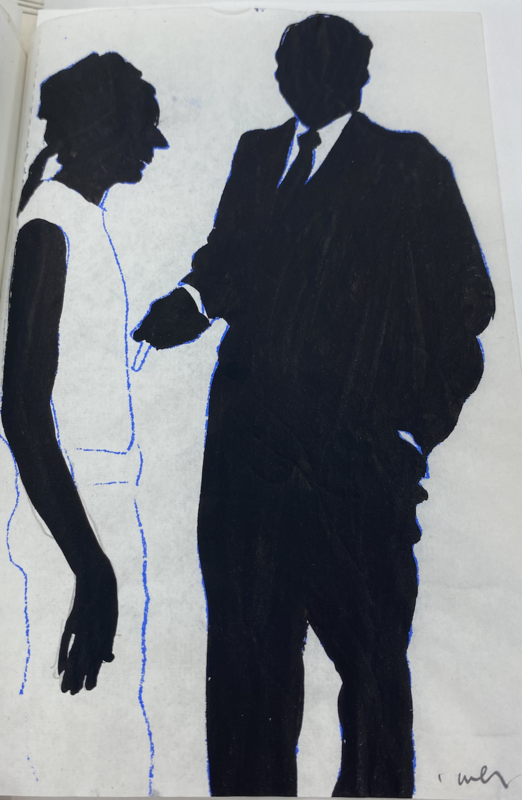

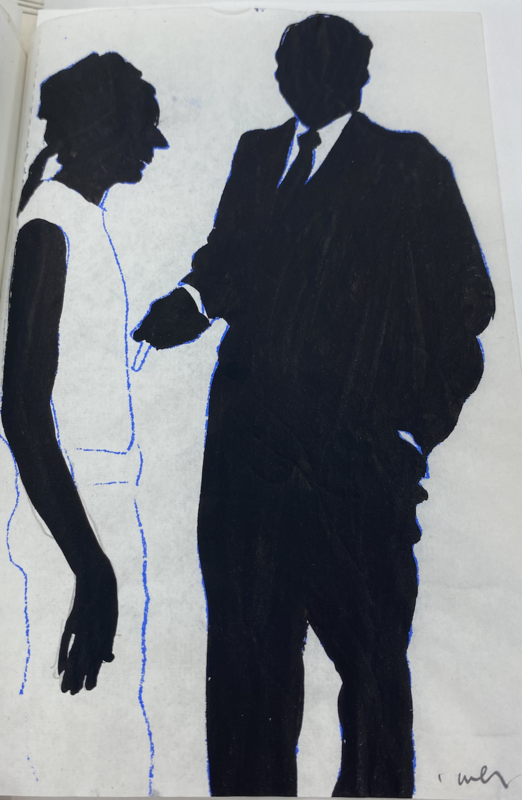

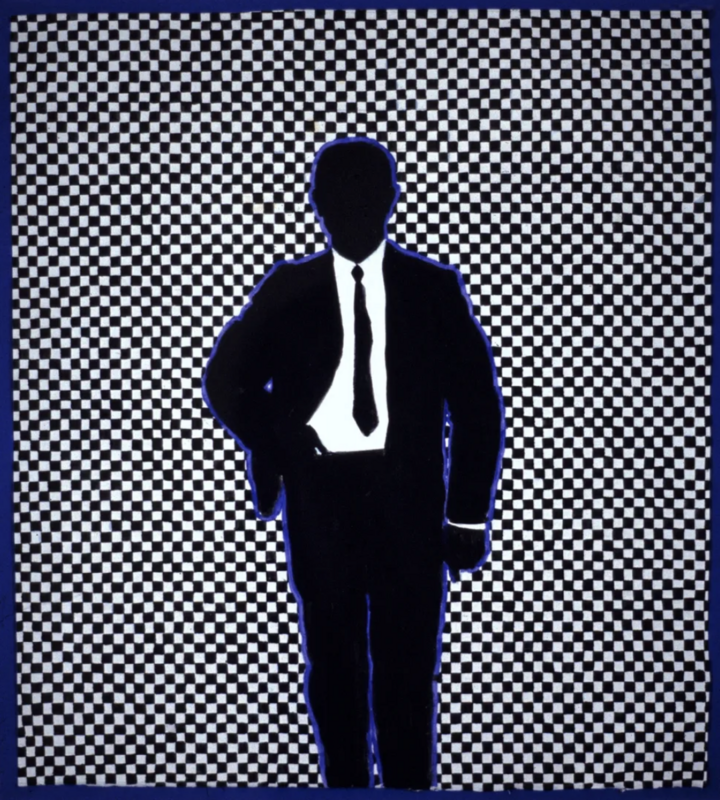

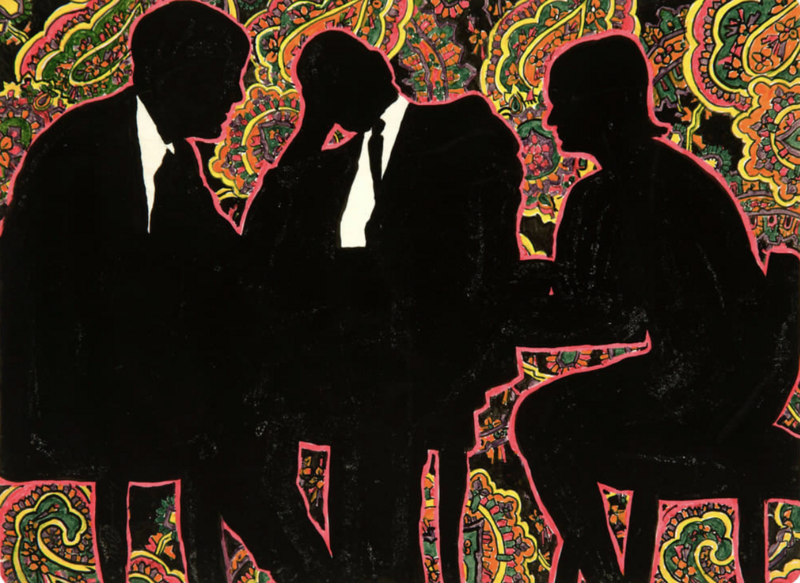

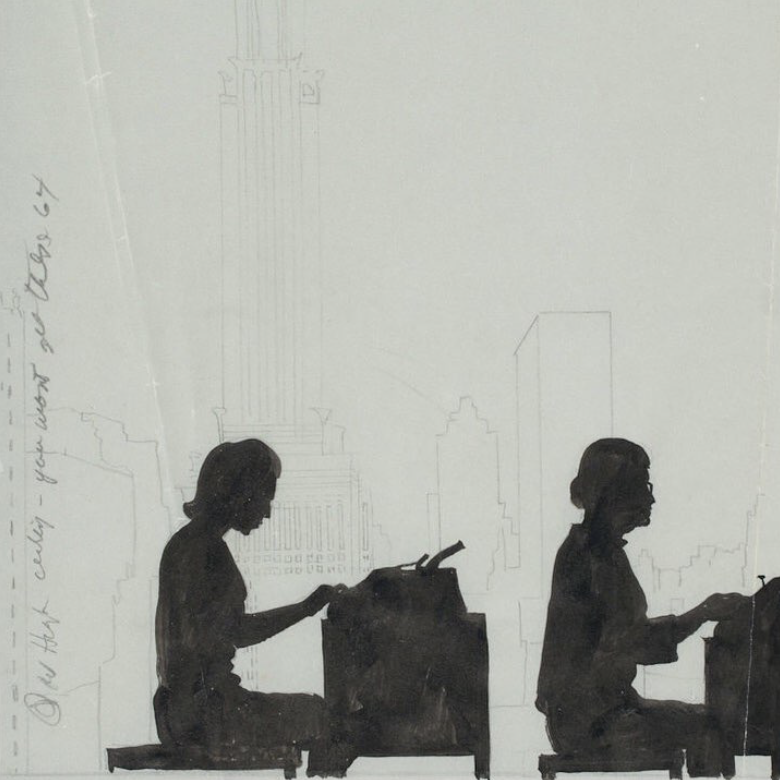

Despite her difficulty in gaining a foothold in her new city, New York reoriented Weber’s way of looking at the world. The white-collar army snagged her imagination. Moved by views into Manhattan office buildings like the one in which her lawyer-husband worked, Weber began painting pitch-black businessmen propelled up and down high-rise escalators, and their female secretaries hunched over typewriters. Her first paintings of businessmen appeared in 1959, and the majority of her work in the coming decade took the form of silhouettes.

In every form – falling nudes, bridal couples, faceless executives – Weber’s silhouettes were a study in lines. Her black silhouettes stood out starkly against a variety of backgrounds: skylines, checkerboards, trellises, solids. Using a blue line, Weber attempted a neon-like effect (see fig.12). She later moved into using neon itself, but soon abandoned the prohibitively complicated and expensive process of plastic sculpting after a lengthy, inconvenient apprenticeship in a New Jersey factory.

Weber’s first solo show was in 1963. She was reviewed well in numerous newspapers and magazines, hailed as the new “Pop-Sibyl.”1 By this time, Weber had known Andy Warhol for several years. She and Julian vacationed with Roy Lichtenstein and his first wife Isabel. Idelle traded pieces with both men, and saved up to buy one of Warhol’s flower paintings. The Webers’ disposable income went toward hiring babysitters every Tuesday and Saturday to attend openings; Idelle lamented that they couldn’t afford to also collect pieces which skyrocketed in value. Warhol attended most of her openings, and she returned the favor.

-

“Idelle Weber,” New York Herald Tribune, May 30, 1964. ↩︎

[Figure 11] Idelle Weber, sketchbook, 1960s. Idelle Weber papers, 1963-1981, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[Figure 11] Idelle Weber, sketchbook, 1960s. Idelle Weber papers, 1963-1981, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[Figure 12] Idelle Weber, “Blue Monday Man,” 1962, watercolor on paper. Art Institute of Chicago. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

[Figure 13] Idelle Weber, “Jump Rope,” 1967–68, plastic and neon lighting. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

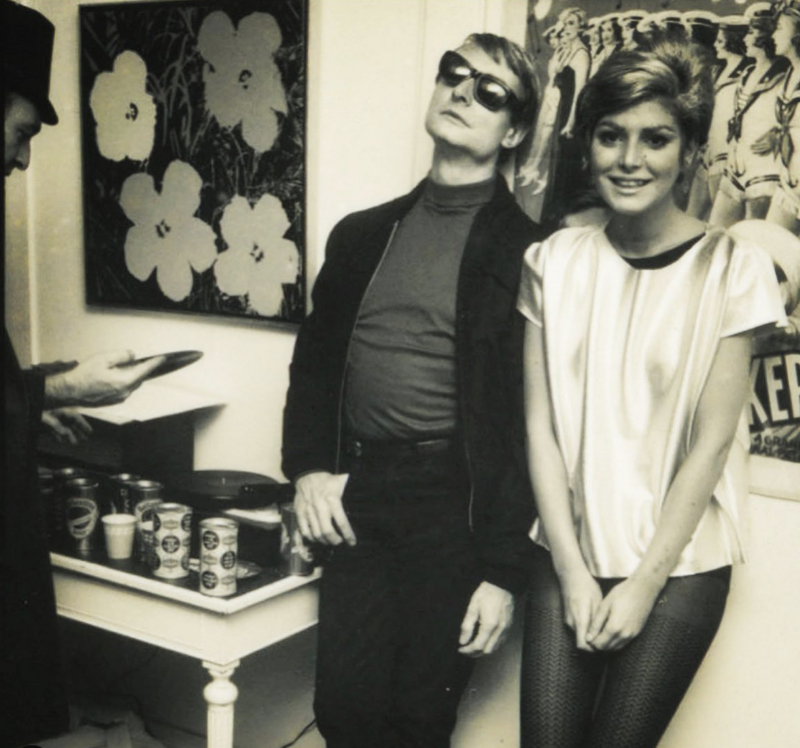

[Figure 14] Roy Lichtenstein as Andy Warhol with girlfriend Dorothy Herzka as Edie Sedgewick at the Webers’ Halloween party, with Ivan Karp and the Webers’ Warhol in the background, 1965. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber.

They did, however, disagree on technique. Whereas most Pop Artists automated their production when they could, Weber never silkscreened or stenciled. Though she often worked on a massive scale, she hand-painted everything, which limited her output. Perhaps her most famous piece is a 17-foot 1964 triptych mockingly called “Munchkins I, II, and III.” When Warhol realized she had hand-painted the tiny black-and-yellow checkerboard background, he chided Weber. She simply replied, “Nuance, Andy, nuance.”1

Pop faded out with the 1960s, but Weber stuck around to survey the scene of an increasingly blighted New York. In the early 1970s, Weber began painting street vendors and their wares in Photorealistic detail pulled from reference images she shot herself – including many left over from her earliest days in the city. Recapturing the excitement and creative drive which her move to New York had occasioned, Weber reinvented herself.

-

Idelle Weber: The Pop Years (New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 2013), 5. ↩︎

[Figure 15] Idelle Weber, “Munchkins I, II, and II,” 1964 acrylic on linen, Chrysler Museum of Art. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber / Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

[Figure 16] Idelle Weber, “Corner Fruit Jungle,” 1974. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In the Gutter

[Figure 17] Idelle Weber, “All City,” 1978. Virginia Museum of Fine Art. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In 1973, Weber secured her first solo show in almost a decade, showing Photorealist paintings of fruit stands. Weber’s close friend, notable dealer Ivan Karp, saw a market for these. He signed her to his Hundred Acres Gallery, where Weber bonded with director Barbara Toll. This had not always been the case for Weber, even with woman gallerists. Stable Gallery’s Eleanor Ward had rebuffed Weber, stating, “We don’t like to show women.” Friend and critic Lawrence Alloway delivered a more crushing blow when he curated an important survey of American Pop for the Whitney Museum. Not only did he exclude Weber, he did not include any women artists. A furious Idelle destroyed many of her Pop canvases.

From grocery storefronts and orange crates, Weber panned the lens of her camera down into the gutter. In a practice which she repeated throughout the rest of her life, Weber began hunting for visually pleasing heaps of rubbish. She captured a city in sharp decline, paying homage to the city’s pervasive and growing filth. And yet Weber evokes something alluring with these pieces, perhaps in response to what must have been a deeply satisfying shift in her practice. In the early 1960s, Weber hustled tirelessly to try to fit the mold of a SoHo art world hostile to her concurrent role as wife and mother. By the 1970s, Weber set her own pace, crossing Harlem and Brooklyn Heights in search of lovely trash while her school-aged children grew increasingly independent.

Weber’s Photorealist work is more technically sophisticated and arguably provides even more incisive critique of American culture. During her Pop days, Weber had avoided commercial products. Her only soup cans came later – empty and rusting, languishing alongside other fallen tin-can soldiers of American commercial empires: Miller, Pabst, Sunkist, Alpo, Goya. Through these remnants of American commercialism, lingering past the end of their useful life, Weber examined the machine of American consumerism which had rendered these products worthless.

[Figure 18] Idelle Weber and City Sanitation Commissioner Normal Steisel at City Hall in 1980, with the newly installed “Lust Set,” 1978, acrylic on canvas. Idelle Weber papers, 1963-1981, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[Figure 19] Installation shot of Idelle Weber’s OK Harris solo show, 1982. Photograph by Eric Pollitzer. From Ivan C. Karp papers and OK Harris Works of Art gallery records, 1960-2014, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[Figure 18] Idelle Weber and City Sanitation Commissioner Normal Steisel at City Hall in 1980, with the newly installed “Lust Set,” 1978, acrylic on canvas. Idelle Weber papers, 1963-1981, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[Figure 19] Installation shot of Idelle Weber’s OK Harris solo show, 1982. Photograph by Eric Pollitzer. From Ivan C. Karp papers and OK Harris Works of Art gallery records, 1960-2014, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Change is the Only Constant

[Figure 20] Idelle Weber, “Jelly Style,” 2001, watercolor on Twinrocker paper. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

For the remainder of her career, Weber pivoted frequently, painting primarily nature scenes. She contrasted the natural beauty of blooms with the sharp angles of flower beds, zooming in on blades of grass and pebbles. In the late 1980s, Weber moved from teaching art at New York University to Harvard. There she created monotype landscapes, taking advantage of her access to a printing press. Weber produced series on gardens, fish, and trees. She rendered images of seashells so precise they seemed computer-generated.

In between, Weber returned to trash again and again. Her pieces implicate us all in the machine of consumerism which takes in the shiny Warholian product, and spits out the empty Weberian byproduct. She weaponizes our brand loyalty and our nostalgia against us.

Weber sketched constantly, almost always portraits – her children and grandchildren, swimmers, sneering women, nudes. Her only major exhibition from this period was 2004’s “Head Room,” a retrospective look at sixty years’ worth of drawings of heads and faces. The 2010s witnessed renewed interest in Weber, as curators investigating the gender politics of Pop rediscovered her work. Weber appeared in important group and solo Pop exhibits. LACMA and the Chrysler Museum bought signature pieces, and her Lucite cubes ended up back where her life and career in New York began – at MoMA.

Weber painted into her 80s. She passed away in the very early days of the COVID-19 pandemic at age 88, having recently relocated from New York to be near family in California. She is survived by both her children and three grandchildren. Julian passed away in 2007 after five decades of marriage.

She had worked steadily, each new pivot garnering her positive reviews in ARTnews in every decade. Despite glowing reviews, unending hustle, and her 2010s renaissance on the public stage, arguably her most recognizable entrée into modern popular culture was uncredited: falling bodies and silhouetted businessmen feature prominently in the opening credits of Mad Men, in an unattributed reference to Weber’s work.

Mad Men made Weber’s silhouettes relevant to a new generation but robbed her of her Warholian fifteen minutes of fame. Her career on and off the canvas, especially in its first three decades, seems to reflect mid-century urban American culture more accurately even than the goings-on at Sterling Cooper. Hovering near the edge of the frame, Weber worked twice as hard as her more famous male counterparts, raising a family while nurturing her career. Glass-ceiling-pounding Weber was for years to the real life, midcentury art world what corporate-ladder-climbing Peggy Olson was to the fictional, midcentury advertising world. Weber chipped away at barriers and stereotypes with a paintbrush, a self-aware combatant of and commentator on misogyny. Her unique, chameleonic career merits another once-over – even if only for the queasy appeal of picking visually through a pile of rubbish for the familiar made foul. In the end, Weber’s comment on contemporary Frank Stella’s work actually befits her underappreciated trash paintings better: “You don’t forget those. You may not like them. And they may be harsh and strident, but there is the visual memory.”

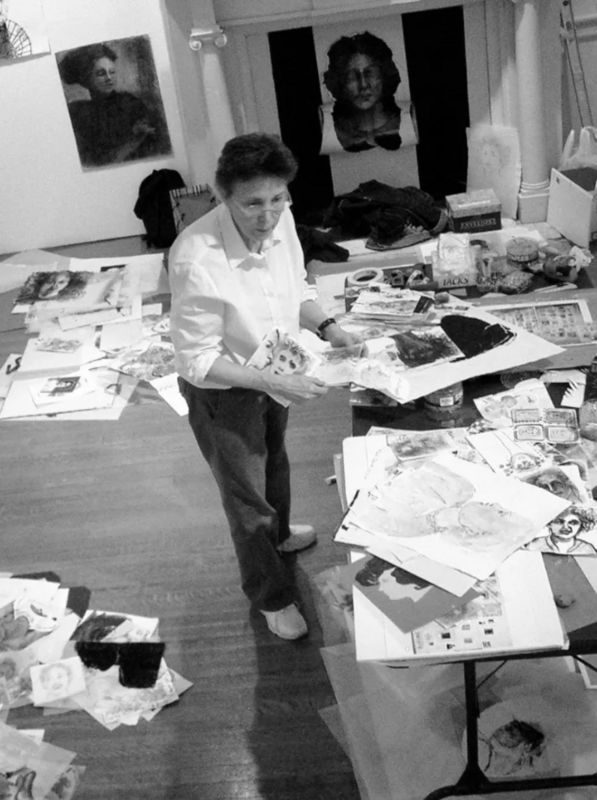

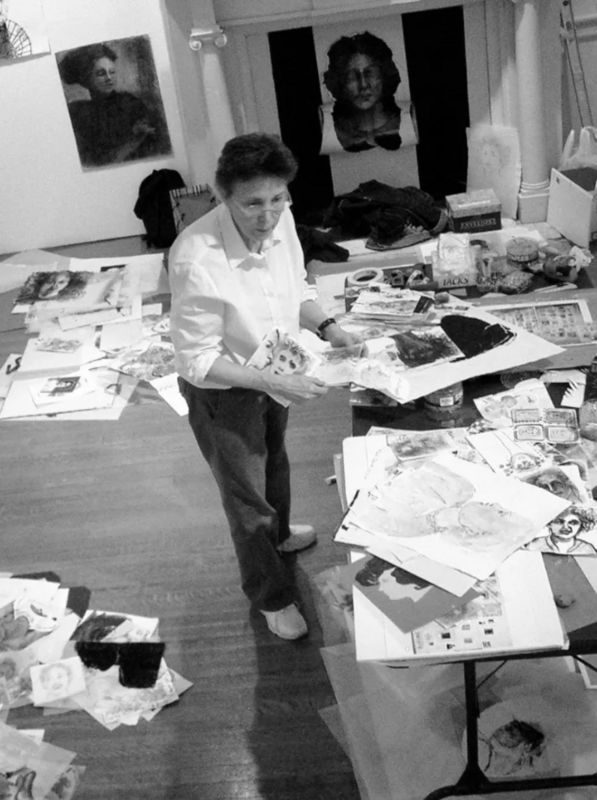

[Figure 21] Idelle Weber at installation of “Head Room,” 2004. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber.

[Figure 22] Idelle Weber, untitled Lucite cubes, 1968-70. Photo by Beth Ann Whittaker Williams, 2023. Museum of Modern Art.

[Figure 23] Idelle Weber, “Livingston Street,” 1964, watercolor on paper. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

[Figure 21] Idelle Weber at installation of “Head Room,” 2004. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber.

[Figure 22] Idelle Weber, untitled Lucite cubes, 1968-70. Photo by Beth Ann Whittaker Williams, 2023. Museum of Modern Art.

[Figure 23] Idelle Weber, “Livingston Street,” 1964, watercolor on paper. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

[Figure 24] Idelle Weber, “High Ceiling - You Won’t Get This,” 1964, tempera and graphite on vellum. Image © Estate of Idelle Weber/Courtesy of Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.